I am writing this short, mostly unsubstantiated rant to help me clarify some of my first steps at reading and thinking about aesthetics and pragmatics in relation to my thesis.

One of the first questions I’m having to answer is why a theoretical abstraction such as aesthetics has anything interesting to bring to a study of the pragmatics of dialogue.

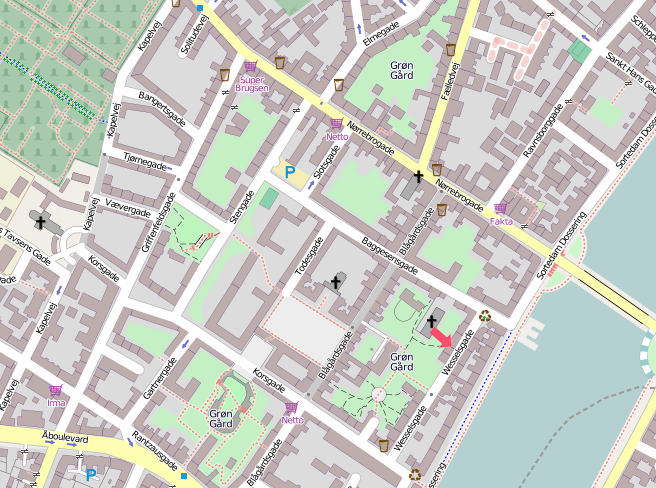

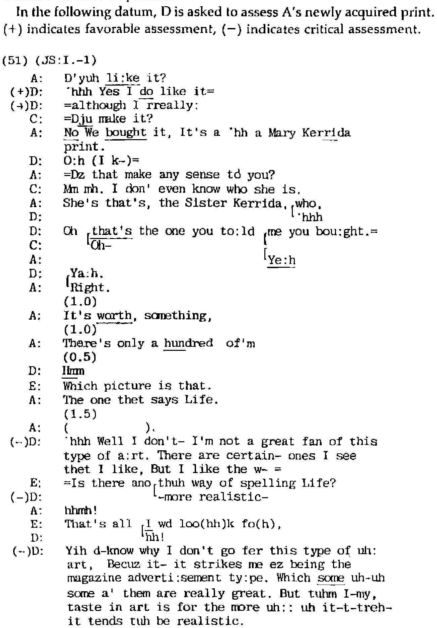

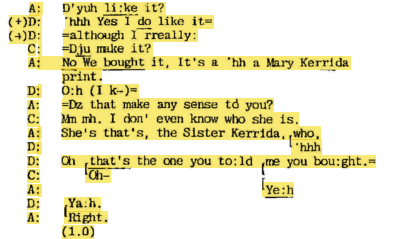

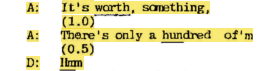

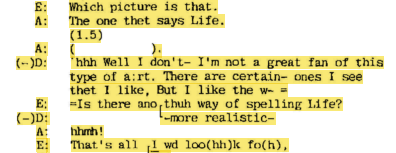

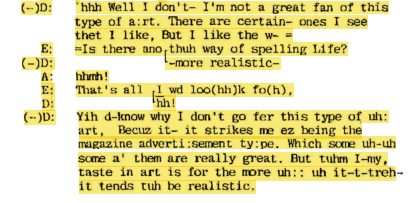

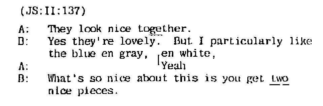

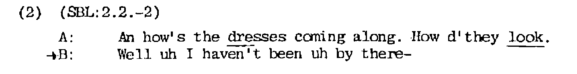

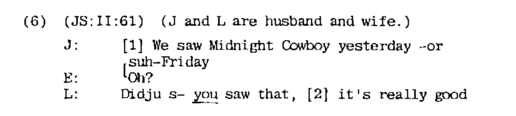

I understand ‘pragmatics’ to refer to a broad set of approaches to the study of human communication and interaction that emphasise the uses of linguistic signs as opposed to their ostensible meanings. For example, conversation analysis (CA), an observational approach to the study of talk-in-interaction involves creating highly detailed transcriptions of the utterances of people in conversation, then asking what they are doing by looking at regularities and exceptions in the organisation of pauses, overlaps, nd the contingent outcomes of their talk in building social action with others. Typically, a pragmatic approach eschews analyses based on a disembodied or decontextualised semantic analysis of what is being said, and by extension, any assumptions or inferences that might be drawn about the intentions or internal, unexpressed emotional or psychological states of the people interacting. Only observable phenomena are considered. What you see or hear, in other words, is what you get.

Aesthetics in the philosophy of art traditionally seeks to determine how we perceive, interpret and judge artworks. In most approaches to Aesthetics, it is assumed that something can be meaningfully described as art, whether by dint of specific formal or perceptual qualities, by historical or institutional conventions, or by virtue of some broader relationships it entails between people, spaces and objects. Because of the high semantic level at which many aesthetic theories operate when compared to the painstaking micro-analysis of communication in pragmatics, these approaches may seem incompatible.

However, what I am arguing here is that aesthetics and pragmatics share a linchpin concept in their uses of ambiguity as a strategy. One of the key concepts in pragmatics is the view that all communication is best understood as an effort to overcome ambiguity. The term ‘speaker-meaning’ is sometimes used to describe what is intended in the production of an utterance. Once the utterance is ‘out there’, however, its meaning to any specific listener becomes analytically ambiguous. The study of talk-in-interaction most often focuses on misunderstandings and breakdowns of communication because often it is only in those instances that any evidence of efforts made to rectify, check or correct the ambiguity becomes observable.

The strategy of ambiguity in aesthetics is a longer and more tortuous story. Aesthetics in the sense outlined above arguably begins with Hume’s and Kant’s epistemological questioning of perception and cognition, and has often returned to a central question of defining art. Although articulating the necessary or sufficient conditions for something to be called art has become a philosophically scorched-earth, it is one of the most enduring and widely engaged-in problems in the field, and is one of the few issues in aesthetics likely to be discussed in a daily newspaper or in everyday conversations about art.

Paul Oskar Kirstellar’s 1951 paper “The Modern System of the Arts” investigated the taxonomy of ‘fine art’ as a distinct set of practices including sculpture and painting but not, for example, basket weaving. This article is often cited as one of the first explanations for the 18th Century formation of the institutions of art and the figure of the artist as an autonomous practice enacted by an individual genius, distinct from the patronage of the church. Kristellar’s explanation that the expanding mercantile cultures of European imperialism shaped the role and the commodity status of the artwork, whether accurate or not, paved the way for a critical re-evaluation of the artwork and the artist as social constructions. For example, critic Arthur Danto’s concept of ‘The Artworld’ (1964) and subsequently George Dickie’s “Institutional Theory of Art” (1969) describes art as a specific set of institutional relationships that determine and regulate the boundaries of what is considered to be art.

These aesthetic theories have a useful explanatory function for describing how, arguably starting with Duchamp, a core activity of artists in this historical/cultural context has been to challenge the boundaries of what can be considered art. The ambiguity of the socially determined status of the artwork is seen as a means of questioning the social institutions that can confer this status. By revealing the ambiguity or arbitrariness of the linguistic/behavioural norms that inculcate the assignment of the art status, by extension artists and their artworks call into question other socially assigned statuses. Since what Lucy Lippard has described as the ‘dematerialisation of the art object’ in the late 60s, contemporary art practices have purposefully manifested a deliberate ambiguity as to the status of their artworks. For example, Warhol’s re-use of pop-cultural artefacts is a direct play on this ambiguity, teasing out the use-value, symbolic and ritual values of brand identities, alongside their ‘special status’ as art objects. Warhol saw the art status as especially useful in that it enabled the oscillation of function and value between the artworks’ statuses and multiple value systems.

Similar uses of ambiguity may have been a feature of, for example, the Baroque trompe l’oeil. However, this recent iteration of ambiguity as a strategy in art seems crucial to an account of how contemporary aesthetic theories and practices position themselves as ‘critical’ or ‘experimental’.

Allan Kaprow’s happenings, John Cage’s compositions, Yvonne Rainer’s street choreographies, all play on the ambiguity of their functions and interpretations as a form of reflexive ontological destabilisation. They intentionally call into question their status as artworks as a component of their expressive or explanatory gesture. The way Kaprow’s happenings unfolded, without a clear beginning or end was central to their power to call into question and into aesthetic/political discourse the activities that occurred before and after the period of their ‘happening’. Cage’s compositions use noise and silence to question institutions of listening. Rainer’s dances problematise normative interpretations of bodily movement.

This destabilisation of art-status is still central to practices of what Pierre Bourdieu describes ‘critical intellectual’, those that question:

“in Aristotle’s sense, notions or theses with which people argue, but over which they do not argue”.

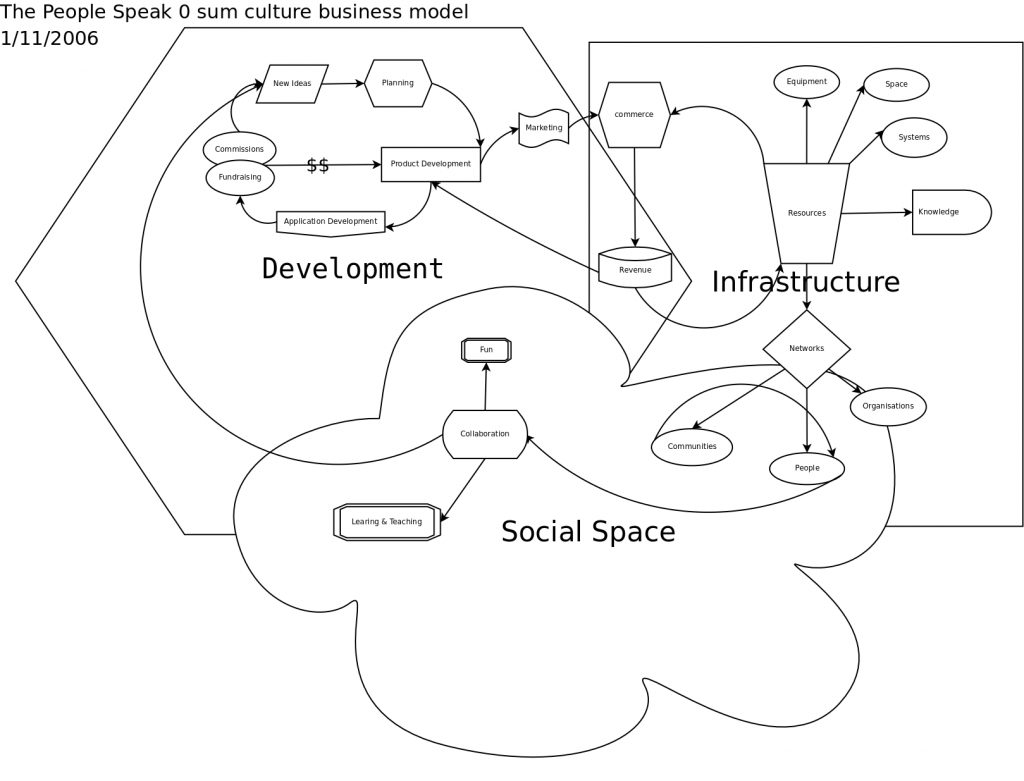

For example, artists such as Sol Lewitt began working with artworks mediated as instructions to be enacted by participants, introducing a further layer of ambiguity as to the relationship between the conceptual author of the artwork and the indexical link between the painter’s hand, brush and wall. Practices such as Art and Language, or the Artists Placement Group in the 70s and 80s, recognising the new epistemic priority of language and interaction in art, extended the logic of dematerialisation of the artwork and its critical functions respectively to focusing on the linguistic means of art’s social production as material, and to its broader institutional relations. Situationist, Mail-art, Neoist, participatory/community art, installation, interventionist and networked art practices have further extended what is often referred to as the dissolution of art into everyday life by applying this status-critique to litigious questions of authorship, revealing the contradictions of legally assigned moral rights to works, the limits of acceptable behavioural and representational norms, and the reflexive, critical refractions of meaning made manifest by the distribution of artworks through systems of governmental or commercial communication.

Alongside visual art and participatory/performance art practices that foregrounded the destabilisation of art and other institutions as linguistically constructed, critical/epic theatre thematised the pragmatics of everyday communication on stage. Brecht’s halting, grating dramatic dialogues are almost faithful transcriptions of the naturalistic fragmentation of discourse in conversation. The way they eschew the conventional theatricality of stage-speak by highlighting the gaps, disjunctures, misunderstandings and half-spoken modes of everyday talk elicits a kind of vertigo response to the ambiguity at the heart of everyday language and interaction. Adorno argues that pedagogical function of Brecht’s plays are to take this vertigo home with them and use it as critical standpoint from which broader social constructions such as political and ideological absurdities.

More recently, artists such as Tino Sehgal have experimented with deploying human interaction as artistic material, introducing performative devices which he and his producer Asad Raza refer to as ‘conceits’ that manipulate face to face communication in specific ways. For example, in his piece “This Progress” in the New York Guggehneim museum, Sehgal empied the gallery of its existing collections, and employed a large group participants to deploy a few specific timed conceits to lead gallery visitors through a series of otherwise impromptu interactions. At one point in the exhibition, Raza describes the visitors approaching a single-person-width corridor, intended as a transition-point between one conversational guide and another. In preparations for the show, after struggling to negotiate the interactional complexity of inviting the visitor to pass through in front of the participant, which invariably led to an unpredictable confusion of politeness, Sehgal found that if they instructed the participant leading the visitors to make a very small, specific gesture, standing adjacent to the entrance, arms by sides, and offering a palm-up forearm gesture, visitors would generally allow themselves to be waved through. This simple gesture is only one in a library of interactional devices, deployed in context-dependent ways in Sehgal’s ‘interactional’ artwork, that treads a fine line between orchestrated and improvised movement and dialogue.

In this context the status-ambiguity of the interaction in which participants and gallery visitors are engaged becomes embedded in the way they talk to each other. A conversation about a gallery visitor’s experience, which in everyday talk might have a certain set of conversational dynamics and characteristics may be modified by unusual conditions (for example, if it is considered and treated as an authored artwork) as it is performed. Although the question of whether Sehgal’s work counts as art is not interesting for a professional aesthetic enquiry, this purposeful fostering of the art-status-ambiguity of human interaction itself makes his practice a tractable subject for interactional research. If pragmatics sees meaning as embedded in the uses of things, then what can we find out about a conversation or an interaction when it is used as art?

Even asking this kind of question seems ridiculous without the specific historical and contextual understanding of ambiguity in art briefly outlined above, and it may turn out that this research in the pragmatics of aesthetics finds no sufficiently solid ground or tractable objects from which to launch an analysis. However, reading Harvey Sacks’ (one of the founders of Conversation Analysis) 1973 paper “On the preferences for agreement and contiguity in sequences in conversation”, there are some striking contemporaneous parallels with Lucy Lippard’s ‘dematerialisation of the art object’.

In this paper, Sacks continually refers to the conversational devices he observes such as conversational turns, sequences of utterances, and even the affirmative token Yeah as conversational ‘objects’. He refers to the complex patterns he finds in talk as ‘machinery’, for example, the “machinery for dealing with misunderstanding” and other “technically interesting objects” or “apparatus” that exhibit “fully formal and methodic potential”. In this way Sacks’ analytic practice transforms ‘materialises’ language as an object of study.

As a deliberate epistemological break from the dominant sociological theories and formal linguistic approaches of the time, Sacks sought ways to materialise language and human communication in order to apply empirical methods to its study. Central to that effort was a recognition of the fundamental ambiguity of human communication, and a commitment to gathering evidence of failures in communication to show how people work to overcome that ambiguity. In the same intellectual climate, art practices that had traditionally ascribed artistic meaning to the objects they produced in relation to traditions and aesthetic theories began to adopt increasingly linguistic or interactional forms and contexts, seeking to build ambiguity into the social material from which their work was made as a deliberate critical strategy.