See the offprint: Albert, S., & Raymond, C. W. (2019). Conversation analysis at the ‘middle region’ of public life: Greetings and the interactional construction of Donald Trump’s political persona. Language & Communication, 69, 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2019.08.001

We’re contributing this talk to Josh Raclaw‘s panel at the AAA 2017 Toward a transdisciplinary coalition in sociocultural linguistics: A collaborative analysis of presidential discourse in Trump’s Black History Month Listening Session. The panel invites scholars from a variety of methodological orientations to address the same bit of data. Our EM/CA-oriented contribution to the panel focuses on the greeting sequences in the first few moments of the meeting.

Chase Wesley Raymond & Saul Albert

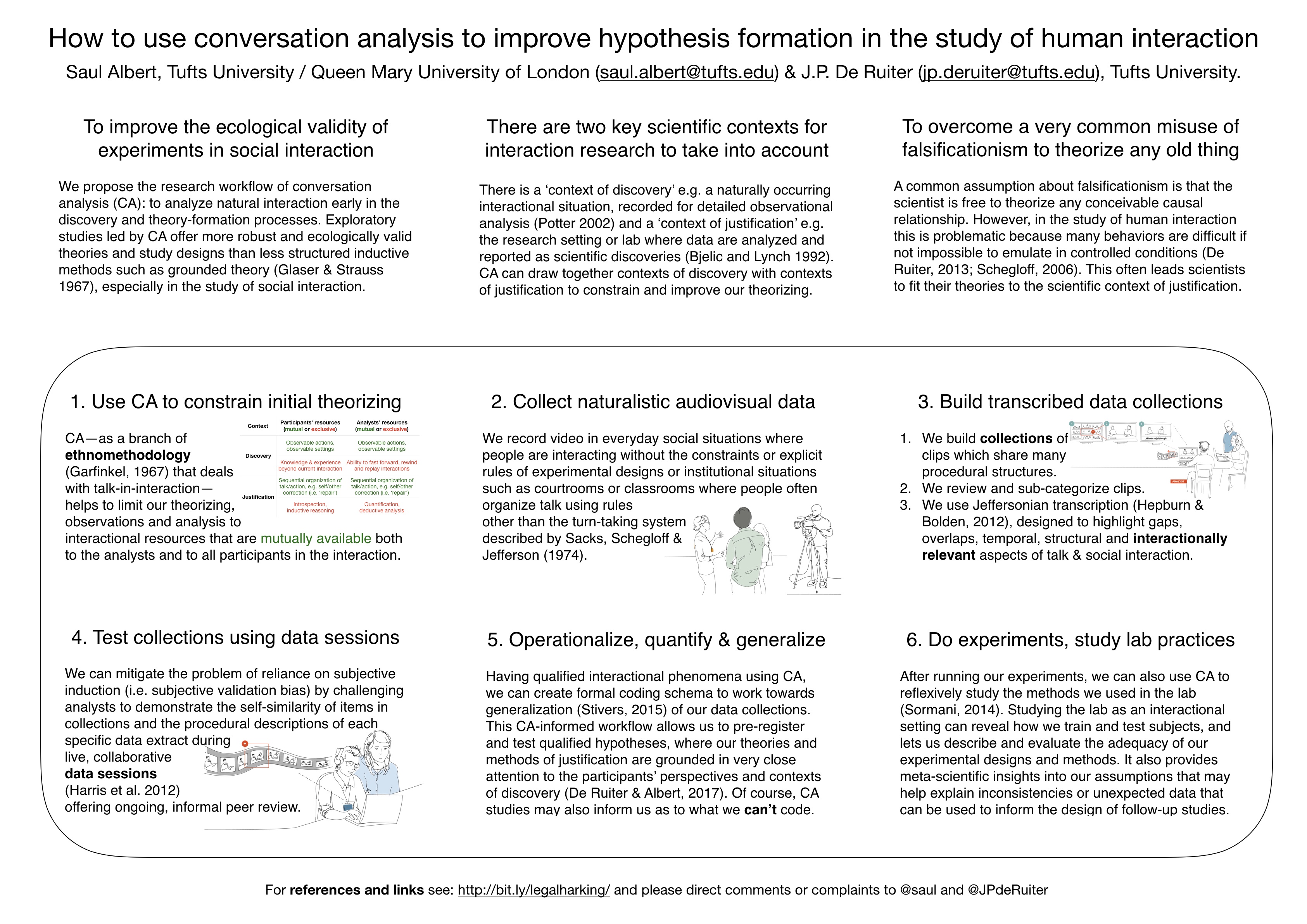

This paper is designed as a contribution to an inter- and trans-disciplinary panel investigating President Donald Trump’s Black History Month Listening Session. Here we adopt the theory and method of conversation analysis (CA) to examine the first minute of this multiparty interaction—from Trump’s entrance into the room, to the launch of his prepared remarks. Greetings and other phenomena that occur during interactional openings have been widely studied from a conversation-analytic perspective (see, e.g., Schegloff, 1968), and yet here we see them occurring in a very particular institutionalized setting, with very particular participants, and in the presence of an overhearing audience (i.e., at-home viewers). In this paper, our aim is to unpack Trump’s initial interactions with those present in the room: whom does he greet, and in what ways, and how is he greeted in return? Moreover, we ask how these greeting practices contribute to the business of “‘doing being’ president” (cf. Sacks, 1984), and thus we will discuss the various membership categories (Sacks, 1992) that are made relevant in and through these brief introductory exchanges. Our analysis therefore offers insights not only into this specific individual’s interactional style and this particular setting, but also into how greetings operate more broadly in multiparty discourse of this sort.

References

Albert, E. (1964). “Rhetoric,” “logic,” and “poetics” in Burundi: culture patterning of speech behavior. American Anthropologist, 66, pt 2(6), 35-54.

Billig, Michael. (1999a). Conversation Analysis and the claims of naivety. Discourse & Society, 10(4), 572-576.

Billig, Michael. (1999b). Whose terms? Whose ordinariness? Rhetoric and ideology in Conversation Analysis. Discourse & Society, 10(4), 543-582.

Bolinger, Dwight. (1961). Contrastive Accent and Contrastive stress. Language, 37, 83-96.

Clayman, Steven E., & Heritage, John. (2002). The News Interview: Journalists and Public Figures on the Air. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Clift, Rebecca, & Raymond, Chase Wesley. (2018). Actions in practice: On details in collections. Discourse Studies.

Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth. (1984). A new look at contrastive intonation. In R. J. Watts & Urs Weidmann (Eds.), Modes of Interpretation: Essays presented to Ernst Leisi on the occasion of his 65th birthday (pp. 137-158). Tübingen: Gunter Narr.

Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth, & Thompson, Sandra A. (2005). A linguistic practice for retracting overstatements: ‘Concessive repair’. In Auli Hakulinen & Margret Selting (Eds.), Syntax and Lexis in Conversation: Studies on the use of linguistic resources in talk-in-interaction (pp. 257-288). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Drew, Paul, & Heritage, John. (1992). Analyzing Talk at Work: An Introduction. In Paul Drew & John Heritage (Eds.), Talk at Work (pp. 3-65). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heritage, John. (1984). Garfinkel and Ethnomethodology. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Heritage, John, & Clayman, Steven E. (2010). Talk in Action: Interactions, Identities and Institutions. Oxford: Blackwell-Wiley.

Hough, Emerson. (1917). The man next door. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

Hansen, A. D. (2005). A practical task: Ethnicity as a resource in social interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 38(1), 63-104.

Jefferson, Gail. (1978). What’s In a ‘Nyem’? Sociology, 12, 1, 135-139.

Jefferson, Gail. (1981). The Abominable ‘Ne?’: A Working Paper Exploring the Phenomenon of Post-Response Pursuit of Response. Occasional Paper No.6, Department of Sociology,: University of Manchester, Manchester, England.

Jefferson, G. (1989). Letter to the editor re: Anita Pomerantz’ epilogue to the special issue on sequential organization of conversational activities. Western Journal of Speech Communication, 53, 427-429.

Kendon, Adam. (1990). Spatial Organization in Social Encounters: The F-Formation System. In Adam Kendon (Ed.), Conducting Interaction: Patterns of Behavior in Focused Encounters (pp. 209-238). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pomerantz, Anita M. (1984a). Agreeing and Disagreeing with Assessments: Some Features of Preferred/Dispreferred Turn Shapes. In J. Maxwell Atkinson & John Heritage (Eds.), Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis (pp. 57-101). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Pomerantz, Anita M. (1984b). Pursuing a Response. In J. Maxwell Atkinson & John Heritage (Eds.), Structures of Social Action (pp. 152-164). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Raymond, Chase Wesley. (2017). Indexing a contrast: The ‘do’-construction in English conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 118, 22-37.

Raymond, Chase Wesley. (Frth). Category accounts: Normativity in sequences of action. Language in Society.

Raymond, Chase Wesley, & Stivers, Tanya. (2016). The omnirelevance of accountability: Off-record account solicitations. In Jeffrey D. Robinson (Ed.), Accountability in Social Interaction (pp. 321-353). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Raymond, Geoffrey. (2018). Which epistemics? Whose conversation analysis? Discourse Studies.

Rossano, Federico. (2009). Gase as a method of pursuing responses. Paper presented at the Annual Meets of the American Sociological Association, San Franciso.

Rossano, Federico. (2013). Gaze in Social Interaction. In Jack Sidnell & Tanya Stivers (Eds.), The Handbook of Conversation Analysis (pp. 308-329). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Sacks, Harvey. (1984). Notes on Methodology. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of Social Action (pp. 21-27). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Edited by Gail Jefferson from various lectures).

Sacks, Harvey. (1987 [1973]). On the Preferences for Agreement and Contiguity in Sequences in Conversation. In Graham Button & John R. E. Lee (Eds.), Talk and Social Organisation (pp. 54-69). Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Sacks, Harvey. (1992). Lectures on Conversation (2 vols.). Oxford: Blackwell.

Sacks, Harvey, Schegloff, Emanuel A., & Jefferson, Gail. (1974). A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation. Language, 50, 696-735.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1968). Sequencing in Conversational Openings. American Anthropologist, 70, 1075-1095.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1987a). Analyzing Single Episodes of Interaction: An Exercise in Conversation Analysis. Social Psychology Quarterly, 50(2), 101-114.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1987b). Between Macro and Micro: Contexts and Other Connections. In Jeffrey C. Alexander, Bernhard Giesen, Richard Münch, & Neil J. Smelser (Eds.), The Micro-Macro Link (pp. 207-234). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1997a). Practices and Actions: Boundary Cases of Other-Initiated Repair. Discourse Processes, 23(3), 499-545.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1997b). Whose Text? Whose Context. Discourse & Society, 8(2), 165-187.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1998). Reply to Wetherell. Discourse and Society, 9(3), 457-460.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1999a). Discourse, Pragmatics, Conversation, Analysis. Discourse Studies, 1(4), 405-435.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (1999b). ‘Schegloff’s Texts’ as ‘Billig’s Data’: A Critical Reply to Billig. Discourse and Society, 10(4), 558-572.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. (2007). Sequence organization in Interaction: A Primer in Conversation Analysis Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schegloff, Emanuel A., & Sacks, Harvey. (1973). Opening Up Closings. Semiotica, 8(4), 289-327.

Stivers, Tanya. (2005). Modified Repeats: One Method for Asserting Primary Rights from Second Position. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 38(2), 131-158.

Stivers, Tanya, & Rossano, Federico. (2010). Mobilizing Response. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 43, 3-31.