Art as occasion: three critical methods for analyzing aesthetic experience

If we want to evaluate aesthetic experiences beyond forms of value we already expect to find, we should look at what people actually do when they experience and discuss art together.

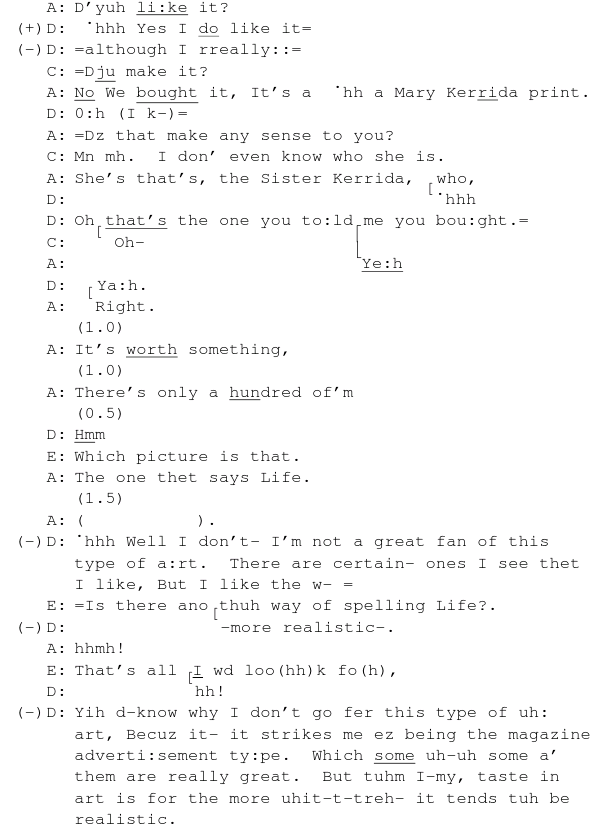

I gave this talk at the 2017 CAA annual conference in Sarah Cook and Charlotte Frost‘s ‘Accelerated art history: tools and techniques for a fast-changing art world’ session. The talk focused on the kinds of things that people say when they’re discussing art, and what we can learn from observing those conversations in order to choose and calibrate our methods of arts evaluation. The main point is that given the basic philosophical problems of using objective measures to evaluate ostensibly subjective experiences, we should use empirical methods such as conversation analysis which are designed for studying interaction and participation to guide the tools and approaches we take to evaluating specific aesthetic experiences and situations.

Data

- Stefan and Katherine: Audio / Transcript.

- Mark and Stuart: Audio / Transcript.

- Lee and Dominic: Audio / Transcript.

References

BNC Consortium (2007) The British National Corpus, version 3 (BNC XML Edition).

Coleman, J.; Baghai-Ravary, L.; Pybus, J. & Grau, S. (2012), Audio BNC: the audio edition of the Spoken British National Corpus Phonetics Laboratory, University of Oxford.

Crossick, G. & Kaszynska, P. (2016), Understanding the value of arts & culture

The AHRC Cultural Value Project, The AHRC Cultural Value Project. Retrieved from: http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/documents/publications/cultural-value-project-final-report/

Hoggart, R. (1957) The Uses of Literacy New Statesman, Transaction Publishers. London, UK.

Pomerantz, A. (1984) in Atkinson, J. M. & Heritage, J. (Eds.) Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes, Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis, Cambridge University Press, 57-102

Stivers, T. (2008), Stance, alignment and affiliation during storytelling: when nodding is a token of affiliation Research on Language and Social Interaction, 41, 31-57

Abstract

Theorists struggle to describe, analyze, and document event-based artwork because its relevance and value seems inextricable from the many varied experiences that involve and therefore constitute the work.

Cultural studies tackles this problem by exploring the social uses of cultural literacy: how artworks may be constituted by a community of use or propagated as mass culture. Critical sociologists of art have shifted focus from the hagiography of artists and cultural canons to diffuse cultural production, distribution, and evaluation processes within specific groups and subcultures. But then which of the situations where cultural works are used and experienced is most relevant? Today, a 90s net.art piece may be viewed on a seat-back monitor in-flight, and early performance, ready-made, or conceptual artworks are often experienced via photographs, retellings in conversation, or as written into art histories. One solution is to treat all social uses of artworks as event-based and therefore analyzable. Recordings of everyday social settings where people engage with artworks in mundane and practical ways can reveal an artwork’s relevance and value in that specific situation. In this talk I plan to demonstrate three critical methodological approaches using three analytic vignettes: two young men shoot and narrate a YouTube video of a performance artwork; two builders discuss Jackson Pollock while plastering a wall; a gallerist and their client flip through an auction catalog. These micro-sociological events reveal the interactional uses of cultural literacy: how people themselves deal with an artwork’s many possible uses and can inform how we should best describe, analyze, and document event-based artwork.

Art as occasion: three critical methods for analyzing aesthetic experience Read More »