Rhythmical coordination of performers and audience in partner dance

What can audience members’ embodied, rhythmical movements tell us about their experience of a musical dance performance? And what do their responses reveal about the composition, organisation and production of the performance itself?

I wrote a paper that focuses on how partner dancers and audience members move together during an improvised social dance performance. The central finding from this paper is a proposal for how we can draw empirical distinctions between improvised and non-improvised (or choreographed) movements.

This important distinction – which if you think about it, is very difficult to describe in theory – can be made in practice by tracking how participants deal with moments where the rhythmical coordination of (in this case) the audience’s clapping, the musical structure and the dancers’ joint movements seems likely to break down.

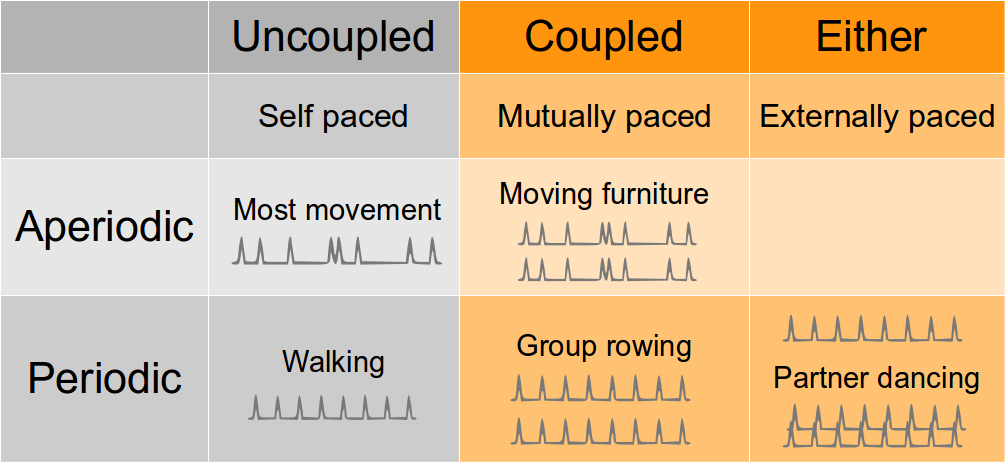

The paper then proposes a way of developing this form of analysis using a model of temporal patterning derived from biological systems.

This approach, combined with analytical methods that are more often used to study conversation and human interaction, shows how researchers can explore the communicative uses of rhythm as a situated interactional resource, and find out, in specific cases and styles, how people build sophisticated social meanings through embodied interactions.

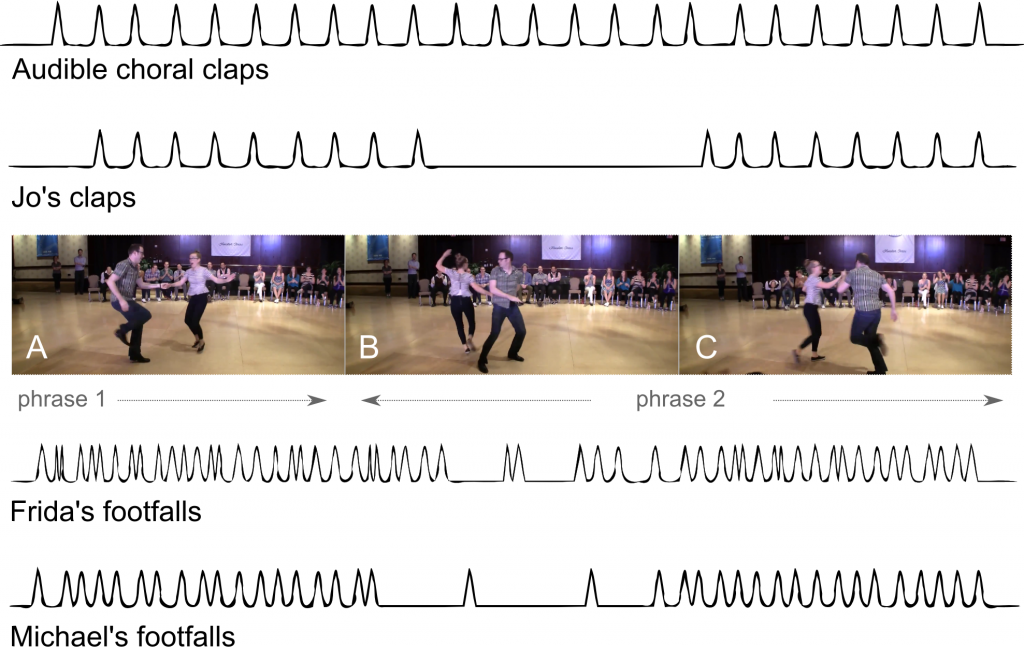

The whole paper consists of a single case analysis of a 10 second clip from a now-classic Lindy Hop Jack and Jill competition performance by Michael Seguin and Frida Sehgerdahl. Here’s the dance in question – the clip starts at 1 minute in, but really – watch the whole thing.

The systematic ways participants in this situation manage disruptions to the audience’s rhythmical clapping in relation to the dancers’ movements shows how they all work to uphold the relevance of normative patterns of mutual coordination. That’s a fancy way of saying that what is considered ‘good’ in this particular partner dance is not some fixed model of perfect dance movement, but the threat (and eventual narrow avoidance) of screwing up. This kind of analysis reveals how dancers initiate, sustain and complete distinct phases of spontaneous movement as embodied social actions.

The analysis in the paper uses detailed, empirical examples of rhythmical coordination to show how dancers and audience members combine improvisation and set-piece choreography. Here’s an example from the conclusion that shows just a few of the rhythmical patterns we can derive from a detailed analysis of just 10 seconds of dancing.

This kind of analysis may not tell us much about the qualitative detail of the dance. However, it provides a clear empirical resource for further analytical work – which can then be analysed in relation to more everyday forms of rhythmical coordination. This provides a starting point for analysing the dancers’ activities and the audience’s response in a way that draws on empirically observable materials that also focuses on the methods the participants themselves use to make sense of those materials.

The approach proposed by this paper shows how people use whatever materials are available including visible, audible and tactile bodily actions as part of a communicative environment. It shows how they can combine these resources in an ad-hoc fashion to coordinate and communicate their movements – much as we do in everyday talk in interaction.

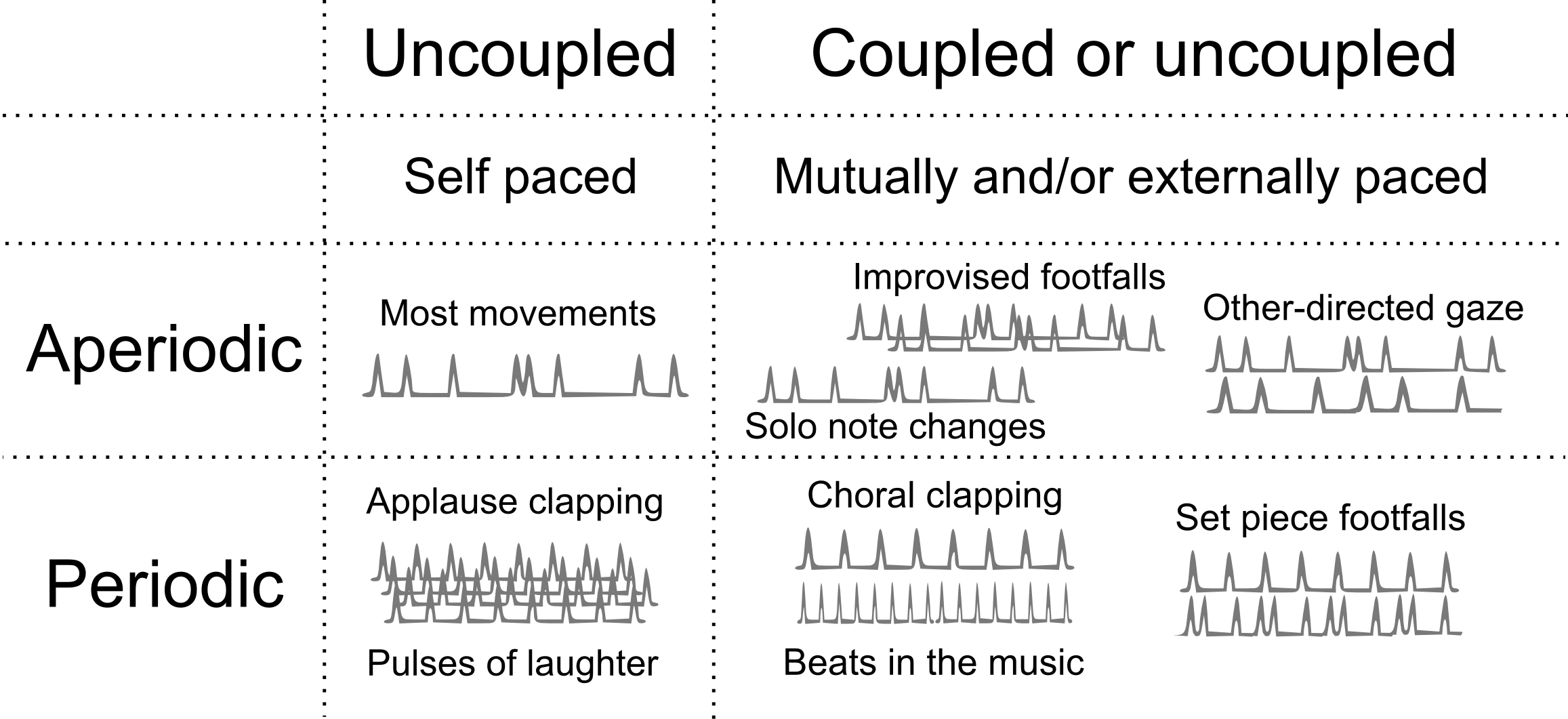

For example, here’s a diagram that shows some of the empirical distinctions we can make about rhythmical coordination in various everyday activities.

Based on this kind of analysis, the paper maps out all the available rhythms in that particular 10 second clip – and shows how they are organised in clearly distinctive patterns.

The purpose, and overall take-away from this paper is that when people talk about the ‘language of dance’, it’s not just an empty idiom, or a transposition of linguistic/semiotic theories onto bodily movements. Dance, seen in its broader social and interactional context, and especially in vernacular dance practices actually functions much like language. In fact, it may be quite difficult to draw clear empirical distinctions between dance, sign language and other forms of communicative social action.

Of course this paper doesn’t go that far – it is intended to set a course for future work as part of a larger project on partner dance as an interactional practice. It suggests that a good place to start understanding the ‘language of dance’ is to look at vernacular practices – where improvisation is combined with set-piece choreography through ad-hoc embodied social action. In particular, the paper suggests that rhythm is one way we can begin to look at dance – and other socio-aesthetic practices – as everyday interactional achievements.

Many thanks to Jonathan Jow and the Lindy Library for the awesome video data. If you want to geek out about it, you can watch another version of the same few moments of dance from a slightly different angle courtesy of Patrick and Natasha. Thanks also to the paper’s two anonymous reviewers, and to Chiara Bassetti and Emanuele Bottazzi for their help and for co-editing the special issue ERQ on Rhythm in Social Interaction in which this paper appears.

Rhythmical coordination of performers and audience in partner dance Read More »