Report from the first EMCA Doctoral Network meeting

I’m on my way back from the inaugural meeting of the inaugural EMCA Doctoral Network in Edinburgh this weekend, which has been one of the best PhD-related events I’ve ever had the pleasure of attending. The last word on the meeting by Anca Sterie (one of the participants) at the summing-up got it absolutely right: the openness, intellectual curiosity and thoughtful care of the organisers and the meeting as a whole was unusual and extremely encouraging.

In any case, I thought it would be useful to document how the workshop was put together, because the format and approach was well worth replicating, especially in a field like EM/CA that can only really progress if people have ways of practising and becoming skilled collaborators in data sessions.

Update: Thanks to Eric for the nice photos!

Before the workshop

The organisers sent us a full timetable before the workshop including a list of readings to have a look at. The readings were two methodology-focussed papers from Discourse Studies:

- Lynch, M. (2000). The ethnomethodological foundations of conversation analysis. Text – Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse, 20(4), 517–532. doi:10.1515/text.1.2000.20.4.517

- Stokoe, E. (2012). Moving forward with membership categorization analysis: Methods for systematic analysis. Discourse Studies, 14(3), 277–303. doi:10.1177/1461445612441534

They also included other authors’ responses to both papers, highlighting methodological differences and challenges.

The sign-up sheet that the workshop organisers mailed around had asked us in advance whether we wanted to do a research presentation or use our data in a data session or both. The timetable made it clear where, when and to whom we were going to be presenting.

Day 1

10:00 – 11:00 Icebreaker:

After coffee and name-badging we made our way into the old library and were allocated seats in small groups of 5 or 6. It was nice to have our names on the tables like at a wedding or something – not a biggie but it made me feel welcome and individually catered-for immediately.

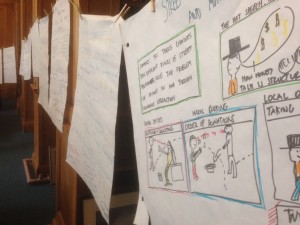

An orientation talk from the organisers Tim Smith and Eric Laurier got us ready to go, then we did a particularly inspired ice-breaker: 20 minutes to use the flip-chart paper and coloured markers on the tables create a hand-drawn poster about our research summarising what we were doing in our PhDs and noting down things we would like help with or wanted to collaborate on. Then the posters were hung up on a long piece of string wound all the way around the room and we had the chance to mingle, grab a coffee and circulate.

The string and posters stayed up throughout and had the effect of making the library feel fun, colourful and informal.

11:00 – 12:30 Reading Session

We then went with our groups to a few different rooms for a reading session where we discussed one of the texts we’d been sent. In my group we discussed the Stokoe text and the responses we’d read. This was a very useful way to meet each other with a common text to discuss that helped us see how we all had quite different responses and were coming from different perspectives.

The choices of methodology papers and responses had been a great idea for this reason: rather than doing the obvious thing of giving us some foundational EMCA papers this choice provided participants from many disciplines with a way to get involved in issues and debates within EMCA.

13:30-15:00 Data Session 1

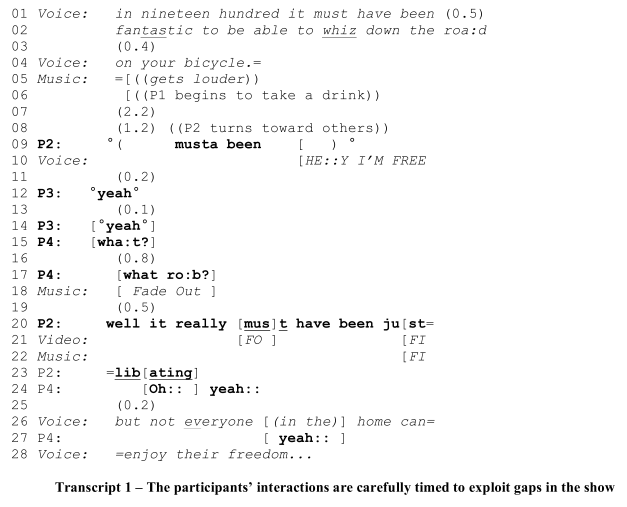

After lunch we got our teeth into the first data session. We broke up into different groups of 5 or 6 and those of us who had signed up to present data got a chance to get feedback and ideas from the wonderful collaborative practice of looking at natural data together.

Some participants hadn’t done data sessions before, but there were sufficient numbers of experienced analysts and in my session Liz Stokoe (the plenary speaker) for the day was on hand to facilitate.

In any case, it was fascinating to see the work that people were doing. Geraldine Bengsch had some great multi-lingual data from hotel check-in counters that really reminded me of episodes of Fawlty Towers. It showed how the humour of that situation comedy comes in part from the interactional contradictions of working in the ‘hospitality industry’. The clue’s in the name I guess: where staff somehow have to balance the imperatives of making customers feel welcome and comfortable with needing to extract full names, credit card details, passports and other formalities and securities out of them.

15:00-16:00 Walk

This was a nice moment to have time to chat informally while having a look around the city or (in my case) sheltering from the pouring rain in a nearby cafe.

16:00 – 17:00 Plenary

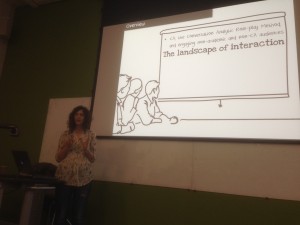

Liz Stokoe then gave a plenary talk that was unusual in that it focussed mostly on her methods of explaining EMCA to non-academics and on the challenges of making EMCA research both public and open to commercial opportunities in communication training with CARM. This kind of talk just doesn’t get done often enough in academia in general. In many fields academics treat discussing ‘impact’ as a necessary evil reserved for review boards, grant justifications and job applications – but never even mention it as part of PhD student training. Stokoe’s talk was open and honest about the challenges and conflicts in this process and it was really useful to see how someone had learned – through repeated efforts – to explain this kind of work to people effectively in non-academic workshop environments.

Although the talk didn’t really relate to the papers we’d read in preparation for the meeting I actually thought this was a much more useful talk in the context than a purely academic presentation. Also, we still had plenty of time to ask Liz questions about her academic research afterwards and over a very nice dinner for all participants.

Day 2

After meeting up for a coffee at around 9 we split up into different groups of 6 again, this time for the presentation sessions.

0900 – 10:00: Presentation Sessions

I was presenting so I only got to see one other presenter: Chandrika Cycil who had some fantastic multi-screen data from her research on car-based interactions focussing particularly on mobile uses of media technologies. There were some lovely recordings of a family occupying very differently configured but overlapping interactional environments (i.e. front-passenger seat / back-seat / driver) together. It was fascinating to see how they worked with and around these constraints in their interactions. For example, the ways the driver could use the stereo was really constrained by having to split focus with the road etc. whereas the child in the front passenger seat could exploit unmitigated access to the stereo to do all kinds of cheekiness.

I also got some really nice feedback and references from my presentation on rhythm in social interaction that I’ll be posting soon.

10:00 – 11:30: Data Session 2

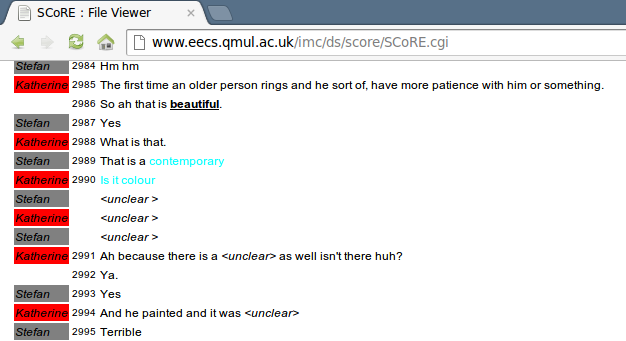

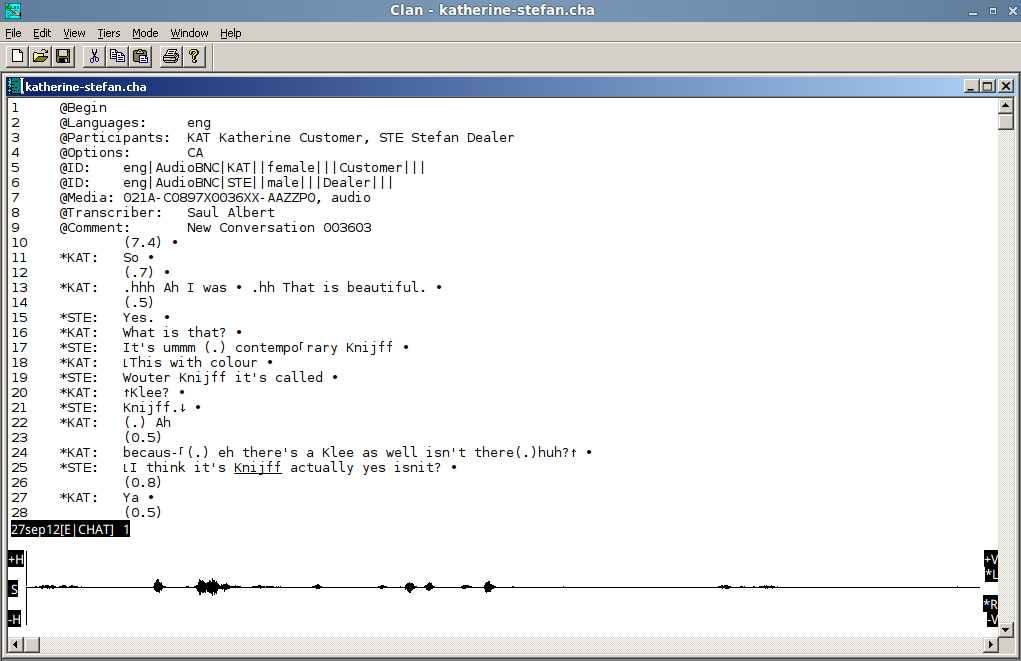

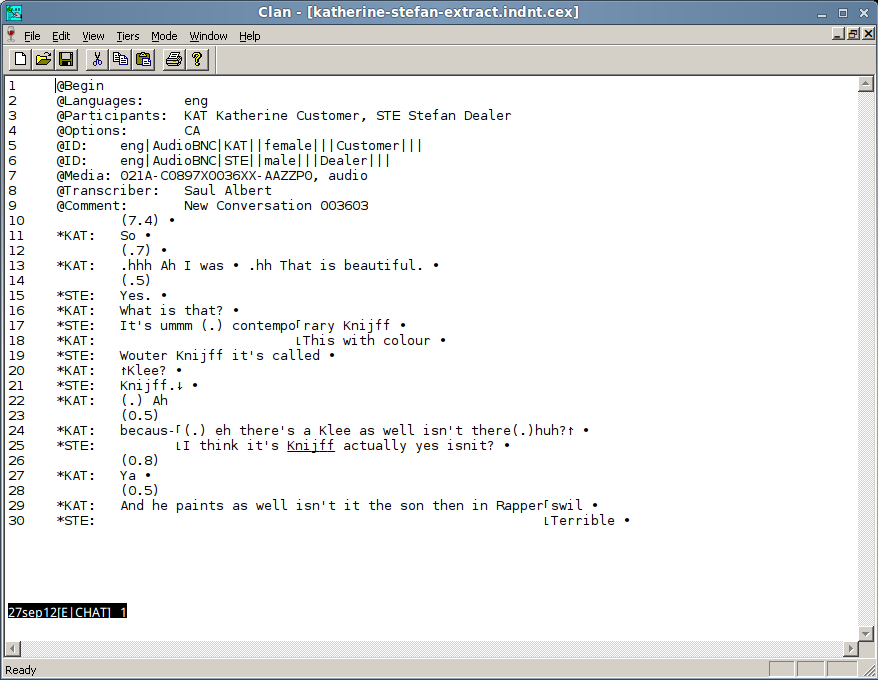

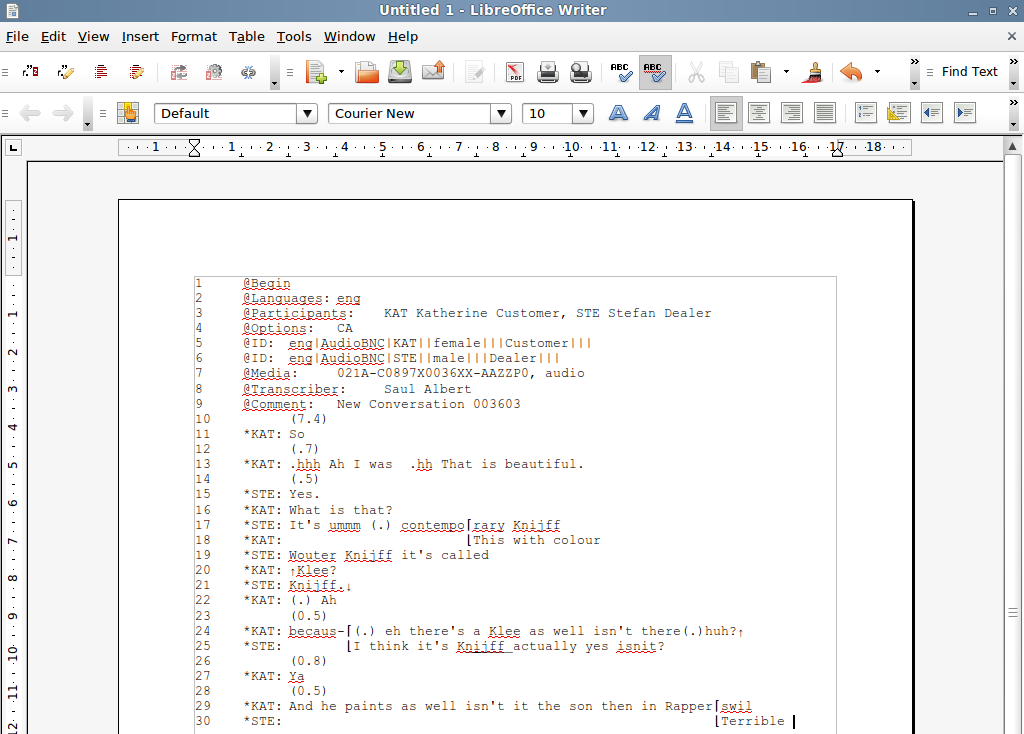

I was also presenting in the final data session. This session – and the meeting as a whole – strongly reaffirmed my affection for the data session as a research practice. There’s no academic environment I’ve found to be so consistently collaborative, principled, and generous in terms of research ideas generated and shared. So – as always in data sessions – I got some amazing analytic ideas from Mengxi Pang, Yulia Lukyanova, Anna Wilson and Lorenzo Marvulli that I can’t wait to get working on.

11:30 – 12:00: Closing review

In the last session we had a chance to give feedback and start planning the next meeting – I think the date we arrived at was the 27th/28th October. If you’re a PhD student working with (or interested in working with) EMCA, and didn’t make it to this one – I strongly recommend putting the dates in your diary for the next one!

Report from the first EMCA Doctoral Network meeting Read More »