Two forms of silent contemplation – abstract for ICCA 2014

Here’s the abstract of my upcoming presentation at ICCA 2014.

There’s a video of the talk with slides here.

Two forms of silent contemplation

- Saul Albert (saul.albert@eecs.qmul.ac.uk)

- Patrick GT Healey (ph@dcs.qmul.ac.uk)

- 25/07/2013

Silent contemplation is often thought of as the canonical form of aesthetic appreciation, a process of solitary reflection during which the qualities of an artwork are apparently absorbed and considered. The ostensibly private, ineffable nature of such moments naturally suggests analysis in terms of individual neural, physiological or cognitive processes. However, one of the earliest achievements of conversation analysis was to show that silences can also be public conversational moves, used to achieve a variety of social actions.

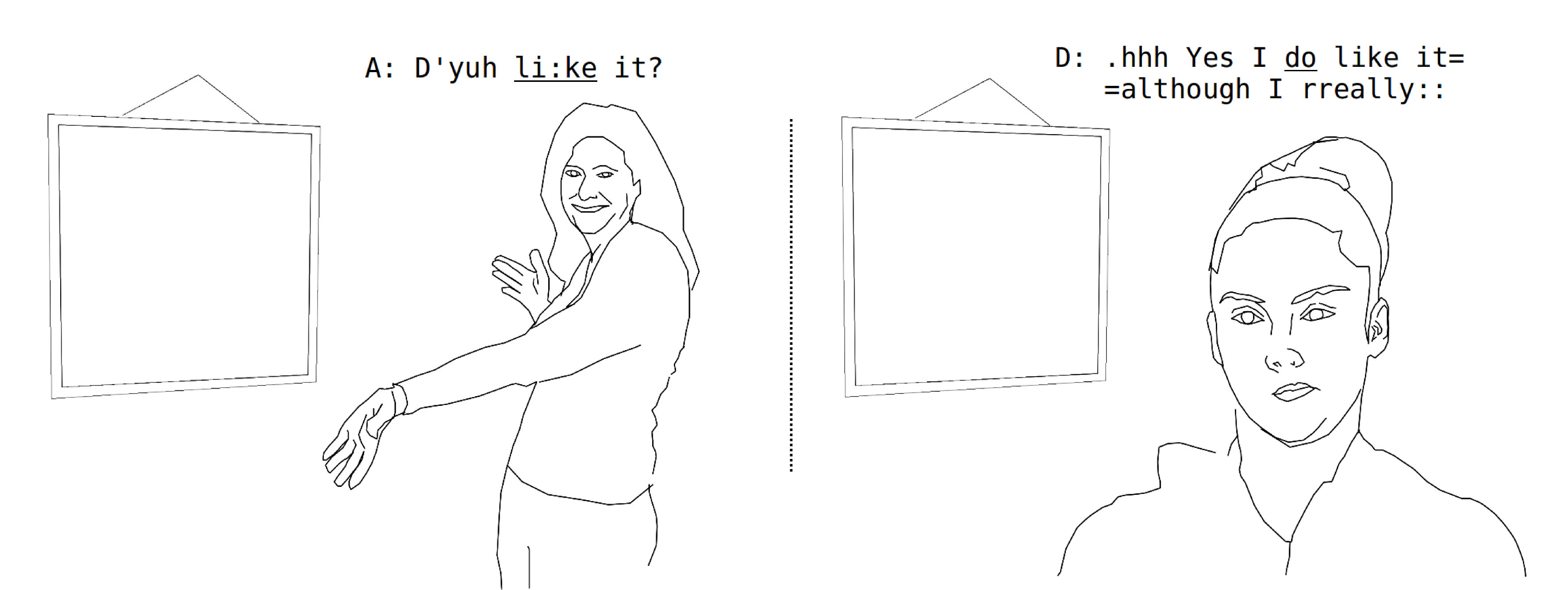

This paper explores the structure of interactional silences in fragments of naturalistic conversation between people discussing artworks in galleries, at home or work, often in a “continuing state of incipient talk” (Schegloff and Sacks 1969). We distinguish between the sequential organisation of two common forms of contemplative silence: one pre-emptively prepared for by a speaker in advance of the silence, and one accounted for and in effect claimed as a contemplative silence by a speaker after the silence has occurred. Here we present an example of the latter form and outline the analytical context.

Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson (1974) introduce silence as a salient feature of conversation especially in relation to turn-taking. They distinguish between the ‘pause’ as an intra-turn silence and the ‘gap’ as a proper occasion for speaker transition, though they also show how these silences are ‘transformable’ in subsequent talk. If a potential gap opens up when a speaker stops talking, it may be transformed into a pause by that speaker resuming. Alternatively, if the gap is allowed to continue in silence, it may occasion a conversational ‘lapse’, which they illustrate with the following fragments in which pauses of 1 and 2 seconds are followed by lapses (indicated by arrows) of 16 and 14 seconds respectively.

(1) (C-J:2)

C: Well no I’ll drive (I don’ m//in’)

J: hhh

-> (1.0)

J: I meapt to offah.

--> (16.0)

J: Those shoes look nice when you keep putting stuff on 'em.

C: Yeah I 'ave to get another can cuz cuz it ran out

(...)

C: Yehhh=

J: =(ok) (2.0) I haven’t not. done anything the whole weekend.

C: (okay)

--> (14.0)

J: Dass a rilly nice swe::der,(.hh)'at's my favourite sweater

on you, it's the only one that looks right on you

C: mm huh.

Both lapses are terminated by J’s assessments of C’s clothes. These are hearable in their sequential positions as ‘first assessments’ (Pomerantz 1984), initiating a sequence of talk by projecting the relevance of some form of second assessment such as C’s minimal agreements “Yeah …” and “mm huh”. Although the first silence in fragment (1) is both started and ended by J, and the second starts with one speaker and ends with another, neither of J’s first assessments post-silence or C’s responses seem to orient to prior talk, suggesting that these silences are heard as discontinuous lapses ended with new topical sequences.

By contrast, in fragment (2), a conversation between Katherine, an art buyer and Stefan, a gallerist, ends in a 7.4 second silence. Katherine re-starts the conversation with a first assessment: “That is beautiful”.

(2) (BNC/KCV/003603)

KAT: a- (.) an o̲l̲d̲er person rings and (1.3) you

sort of:f (1.7) tch .hhh (1.8) haff more

p̲a̲t̲ience wizz him or something.

(7.4)

KAT: So

(.7)

KAT: .hhh Ah I was .hh That is beautiful.

(.5)

STE: Yes.

The initial assessments in both fragments (1) and (2) are not randomly inserted into the talk. Rather, as Mondada (2009) suggests in her analysis of food-talk in dinner conversations, such assessments are systematically used as a resource for relaunching conversation after a lapse or a troublesome spate of talk.

However, a closer look at fragment (2) demonstrates that while Katherine’s assessment accomplishes re-initiation of talk, prompting a minimal acknowledgement from Stefan, it does so in a way that seems to orient towards the preceding pre-lapse talk. Her initial “So”, suggests an incipient development of the prior topic [@Raymond2004], then her halting self-repair seems to be initiating a retrospective self-attributed account: “.hhh Ah I was .hh”. Finally Katherine produces “That is beautiful” hearable as both a first assessment, but possibly also as an account for the potentially troublesome 7.4 second lapse.

This post-lapse initial assessment can be seen to accomplish several actions simultaneously, including re-launching the conversation, but also asserting a retrospective claim to the prior lapse as a silence that is attributable and accounted for as contemplative.

This brief outline concentrates on only one way in which one form of contemplative silence is produced. Building on this analysis, we propose that silences in conversation can, in some circumstances, be shaped in different ways and to different extents for response (Stivers and Rossano 2012) and are treated by recipients as distinctively cognitive events in that ostensibly private internal processes are made manifest on the surface of the conversation.

A short review of other analytical approaches to conversational silence informs a discussion of whether contemplative silence may be seen as specific to contexts such as the joint viewing of artworks. We conclude that social practices of contemplation are generally available to participants in everyday conversation, and sketch out some of the implications for empirical and theoretical research into aesthetic response.

References

Mondada, Lorenza. 2009. “The methodical organization of talking and eating: Assessments in dinner conversations.” Food Quality and Preference 20 (dec): 558–571.

Pomerantz, A. 1984. “Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes.” In Structures of social action: Studies in Conversation Analysis, ed. J. Maxwell Atkinson and John Heritage, 57–102. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Raymond, Geoffrey. 2004. “Prompting action: The stand-alone ’so’ in ordinary conversation.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 37: 185–218.

Sacks, H., E. A. Schegloff, and Gail Jefferson. 1974. “A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation.” Language 50: 696–735.

Schegloff, E. A., and Harvey Sacks. 1969. “Opening up closings.” Contract 49.

Stivers, Tanya, and Federico Rossano. 2012. “Mobilising response in interaction: a compositional view of questions.” In Questions: Formal, Functional and Interactional Perspectives, ed. Jan Peter de Ruiter, 70–90. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Two forms of silent contemplation – abstract for ICCA 2014 Read More »