In the Internet of Things, what kind of thing is your TV? And what kind of thing are you?

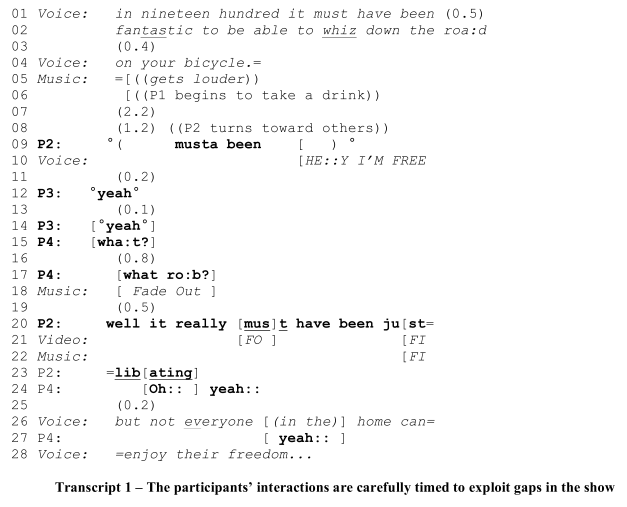

Researchers designing ‘Social TV’ used conversation analysis to look at how people interact while watching TV (Oehlberg, Ducheneaut, Thornton, Moore, Nickell, 2006){{1}}. They found that viewers integrated the TV into the conversation, making space for it to ‘take turns’ in much the same way as any other conversationalist.

Although the TV is traditionally quite a selfish conversationalist, speaking more than listening (unless you explicitly shut it up with the remote), the prospect of it becoming a more accommodating conversational participant as a networked device is intriguing. For example, when your Boxee remote app on your iphone detects an incoming phonecall, it will pause your TV. That’s not an especially complex interaction, but it points towards the possibility of the TV at least brokering conversation in a more fluid way by letting other devices (your iphone in this case) participate in turn taking.

It would be interesting to see whether a TV that politely paused itself when it detected a sufficiently high level of chatter in the room would encourage or discourage further communication. I suspect the former – like a schoolteacher adopting patient silence with pursed lips while the children settle down. It would be a fun thing to experiment with though.

But the real promise of networked TV is that it becomes more than just a turn-taker, and begins to participate more actively in the conversation.

Perhaps not quite as actively as that, but there are some amusing parallels between some of the proposals for future TV services and the TV-becoming-flesh in Cronenberg’s Videodrome.

For example, some of the most interesting social TV research I’ve found so far – namely the notube project has looked at ways of leveraging network technologies, linked data and Semantic Web strategies for enriching TV viewer’s experience.

Their ‘beancounter’ application uses a variety of sources including social network platforms, to aggregate data about what you’re watching and creates a detailed, machine readable profile of your habits. This profile can then be used to generate better recommendations, or even help to inform and improve your experience of viewing and discussing media. The really difficult bits of this problem – like trying to figure out what is actually being talked about are dealt with gracefully, using ‘good enough’ systems that evaluate multi-lingual natural language text strings and suggest concepts that they may refer to. Ontotext’s LUpedia service provides this entity recognition function for notube. {{2}}

But in a home, where the TV is in a shared space, does the TV learn from each member of the family separately? From listening to discussions at BT, I’ve learned that the ‘problem’ of knowing who is watching the TV, in order to recommend relevant and appropriate content is not going to be solved by having each watcher cumbersomely log in to the TV. Nor is it going to be entirely solved by logged-in or sensed 2nd screen companion devices (not everyone will have one). BT’s immediate strategy will apparently involve a more complex watershed, where what people watch at certain times of day will inform assumptions about who is watching, and what kinds of content to recommend. Communications companies just don’t have this level of access to monitoring our individual behaviours within the home, and there are probably serious privacy and consent implications that will be significant barriers to granting it to them.

And anyway, I’m more interested in what kind of device the TV becomes when it learns from our collective viewing habits, aggregate viewing behaviours and networked discussions. Does the networked TV begin to develop a compound user profile of it’s own? A unique combination of a household’s various proclivities? Is it like the family dog, which everyone interacts with individually and collectively, and is then seen as having a personality, to some extent nurtured through this process.{{3}}

This brings me back to the idea of the TV as a conversational participant. If it can develop a profile, and start to build a model of the various areas of interest and domains of knowledge that a user is interested in, can it participate in a conversation in a more complex way than turn-taking? One of the key ideas of conversation analysis is the notion of ‘repair‘, in which the contingent meanings of utterances between conversational partners are narrowed down and cross-checked for mutual comprehension through all kinds of gestural or verbal cues and repetitions.

Can the TV begin to engage in this level of conversation? Can it’s profile of established interests be used as a source of recommendations that might clarify a misunderstanding of something that has just been said, for example, correcting the misidentification of an actor by people chatting about what they’re watching together on facebook{{4}}. Or could it relieve the co-watcher’s burden of responding to annoying whispered questions during films (‘why is she holding that chainsaw?’) by delving into more complex layers of in-programme dramaturgic medatada and providing some suggested explanations{{5}}.

Can the profiles of individual viewers and their shared TVs then be evaluated quantitatively for similarities over specific periods of time as a measure of the effectiveness of this kind of conversational grounding with various types of content and TV format?

And at what point do we reach the threshold of complexity, fluency and multi-valency beyond which these kinds of interactions with your TV can be thought of as a conversation?

[[1]] Oehlberg, L., Ducheneaut, N., Thornton, J. D., Moore, R. J., & Nickell, E. (2006). Social TV : Designing for Distributed , Sociable Television Viewing. Theater. [[1]] [[2]] I think of this as graceful because it addresses a hugely complex set of contingencies in a simple and contingent way, by issuing a query to a good enough service via a standard API, that does something useful, and assumes that in the future, when there is more linked, semantically enriched data, and more advanced inference services available, the API can just be plugged into those. [[2]] [[3]] I’m aware that this idea that pets do not have Disney-like anthropomorphic personalities is not popular, especially with British people, and I’m not backing it up with anything other than my own supposition that this is the case, and that your animals would eat you in a second if they were hungry enough and you were incapable of defending yourself. [[3]] [[4]] In the lingo of conversation analysis this would be called ‘self-initiated self-repair’ [[4]] [[5]] Other-initiated self-repair [[5]]

Interesting. I don’t have the actual transcript of the conversation from last night around our TV set (I can only guess… not sure I actually want to see it, though… reminds you of how last night was totally wasted).

Interactive TV has a long tradition, you know. Just look up the ‘Winky Dink’, an American Children’s program from the fifties, and you will see the host trying to stage a conversation with the children pretending to see them and having them make drawings on their TV set for him (special celluloid screens were sold for this). Also, the man who invented the game console, Ralph Baer was originally working for a TV manufacturer and started wondering what you could do with the thing when nobody was broadcasting. This was in the early sixties I believe, but he didn’t get around to make a prototype until 1966 (‘The Brown Box’). This eventually turned into the first commercial game console in the early seventies (‘The Magnavox Odyssey’ – really cool design object). There are other weird ideas of ‘interactive’ TV and using the TV set for other kinds of interaction too.

I guess that the idea of having a conversation with your TV in reality turned out to be a cybernetic feedback loop in games – where the TV actually watches and responds to you. You could maybe even argue that the game console really is a ‘family dog’ as you suggest.

Well, just some trivia…

‘Winky Dink’ made my day. Thanks Christian!