On 7th-10th May 2009, the Undoing The City festival was held in Copenhagen, consisting of discussions, walks, screenings, talks, performances, street actions and exchanges between artists and activists from around the world with the shared aim to “make the city a common space”.

The festival came to public attention when, during a post-festival street action, a group equipped with a sound system, ladders, paint and ropes barricaded themselves into Hyskenstraede, just off one of Copenhagen’s main shopping streets, and as police stood by, some sub-groups danced and partied while others watched, snapping photos on their mobile phones while others torched cars, smashed shop windows, and covered every surface of the street in colourful, Situationist-inspired graffiti slogans.

Almost immediately, newspapers and TV reports spread the story and war-zone-like images world-wide, thousands of people diverted from their shopping trips to snap photos of the damage, uploading hundreds of photos to social media sites and writing about the event and ensuing controversies about the funding of the festival and its political supporters.

Three years later, the impact of this event is still very visible in how the street is represented online. Alongside images of shops and products, images taken by passers-by, shoppers, journalists and bloggers still form a prominent visual trace of those events.

The following day, artist Jakob Jakobsen led a two hour workshop: Nørrebro Åben By (Nørrebro Open City) during which participants walked with GPS devices and paper print-outs of out-of-copyright topographic street maps of the area. The aim of the workshop was to survey and draw-in the peaceful courtyards and urban gardens that were increasingly being gated and privatised as the Nørrebro neighbourhood underwent a rapid gentrification process, and then upload them to OpenStreetMap, a “wiki world map” based on a repository of user-collected copy-left geodata.

“We held a party that doesn’t exist. And we left some traces that existed –for some”

– Os der Ikke Findes (We who do not exist)

After three days of intense media debates about “riots”, three communiques from self-proclaimed party organisers appeared on the Internet, reacting to some of the immediate criticisms about the “heteronormativitiy” of street action and property damage – the idea, expressed at discussions following the event that those actions in themselves are both gendered and class-determined, in effect luxuries of ‘political’ expression exclusively accesible to those who least fear the possible consequences. The communiques also expressed a kind of gleeful eroticism in the occupation and temporary transformation of an urban space:

“The traces are rough. They are proof of that we have had sex up one street, down Stroeget, through the market. They run fifty meters down an infinite city that does not exist, but is owned by someone else”

John Pløger draws on the organisers reference to Foucault’s concept of “Heteratopia” to describe their use of a “presence aesthetic” of sensation, emotion and perception brought about through “the eventalisation of a temporary urban space” (Pløger, 2009, pp. 864), to create a representation of the heterotopic “multiplicity of uses and use-values” of a specific urban space. He argues that this representation is intended to inspire a multiplicity of interpretations and uses of an otherwise highly commercialised shopping street. Ironically, he also points out how this representation of the city could be seen to appeal to Copenhagen’s countercultural tourist trade.

Walking down Hyskenstraede the day after the riots, the profusion of tourists taking photos and milling around the shops supported this analysis. Like parts of “Fristaden Christiania”, a legally distinct neighbourhood of Copenhagen built on an ex-military base, squatted in the 1970’s and the site for significant counter-cultural and drug-related activity, the graffiti and the excitement of entering an area bearing the ‘traces’ of transgressive behaviour drew a huge amount of attention from tourists and locals alike.

The staff in Natuzzi, a luxury furniture dealer that had been one of the most enthusiastically vandalised of Hyskenstraede’s shops were perpexed by the fact that despite the damage, and having had one of their sofas burned in the street, they had experienced the most successful day of trading so far that year. They pointed out several long, expensive beige sofas daubed with vivid blue streaks of spray paint and explained that they had sold all the graffiti-damaged stock almost as soon as they opened that morning. The discerning furniture-buyers of Copenhagen were presumably sensitive to the enahnced value of a sofa that had seen authentic political action, not to mention that the electric blue did go rather well with the beige leather.

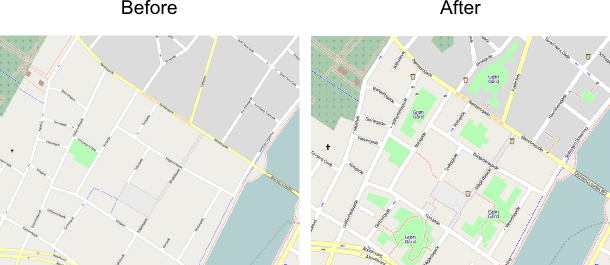

Though less mediagenic than the graffiti and broken glass that decorated Hyskenstraede for a few days, Jakobsen’s one-off Nørrebro Åben By workshop also left traces in the city, inscribed in the geographical data that represents the neighbourhood on OpenStreetMap. These traces, constituted by magnetic alignments of bits and bytes on networked computer media, downloaded onto navigational devices, integrated into mapping systems or printed as copyright-free maps have, arguably, become a far more persistent and widespread expression of the heterotopic ideals apparently espoused by the Os der Ikke Findes street party.

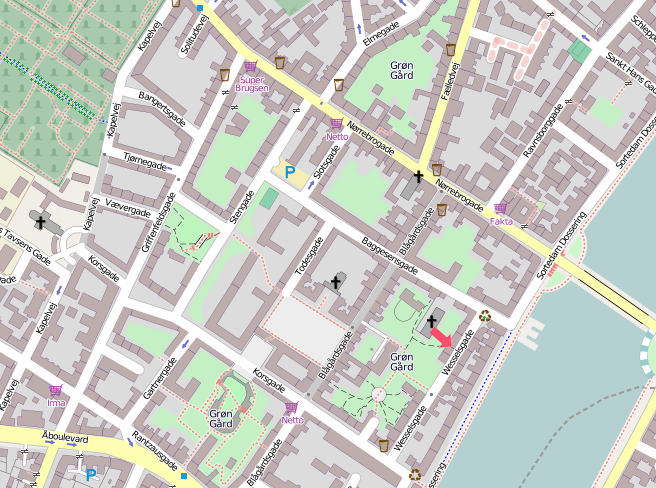

This snapshot of the OpenStreetMap showing the same area of Nørrebro taken in in April 2012 shows how much more complex and detailed the user-generated map of the neighbourhood has become, still showing the tiny gardens and passageways mapped during the Nørrebro Åben By workshop in May 2009. Zooming out shows that the presence of these inner courtyards as mapped spaces in the city are a distinctive feature of this neighbourhood. Nearby areas have far fewer of these kinds of spaces, and maps of the area created using commercial geodata from Google Maps have none of these idiosyncratic features:

These two representations of the city: the traces, photographs, news items, blog posts and online media left by the street party on the one hand, and the quiescent accumulation of user-generated geodata on the other are useful starting points for an analytical account of how representations of the city, and struggles over its uses and use-values have adapted to the advent of networked ubiquitous user-generated online media and geographical information systems.

References:

Pløger, J. Presence-experiences—the eventalisation of urban space Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 2010, 28, 848-866