How to share large amounts of research video data with Syncthing

One of the major logistical problems facing researchers who use large audiovisual data files featuring recordings of human subjects is how to share it with colleagues simply, securely and inexpensively.

- By simple, I mean that the a/v file-sharing solution should not need specialized equipment or an expert systems administrator to set it up for you. Most universities and research institutions have in-house research file servers. These may be security audited, up-to-date and well-organized – they may seem unlikely to suddenly lose or delete all your data or randomly restrict access to your colleagues in other institutions. However, in my experience, it’s best to manage your own data and backups!

- By secure I mean that it should not rely on cloud-hosted storage (which may store and transfer data anywhere in the world), or allow data to be transferred unencrypted between remote systems. This is often a requirement of UK human subjects/ethical approval – so it’s particularly relevant in the case of UK educational institutions, but this is probably also true elsewhere.

- By inexpensive I mean that it should not cost the end-user an ongoing fee, or meter use per gigabyte stored. Commercially available cloud file-storage services like Dropbox, OneDrive, Google Drive or iCloud are relatively cheap up to ~ 1TB storage, they can get quite expensive beyond that, and if you have multiple projects with multiple researchers in different groups sharing data – the total cost for all researchers can become prohibitive.

There are trade-offs between these three requirements – this blog post outlines how to use Syncthing – which I think is an optimal solution – to solve this issue.

What is Syncthing?

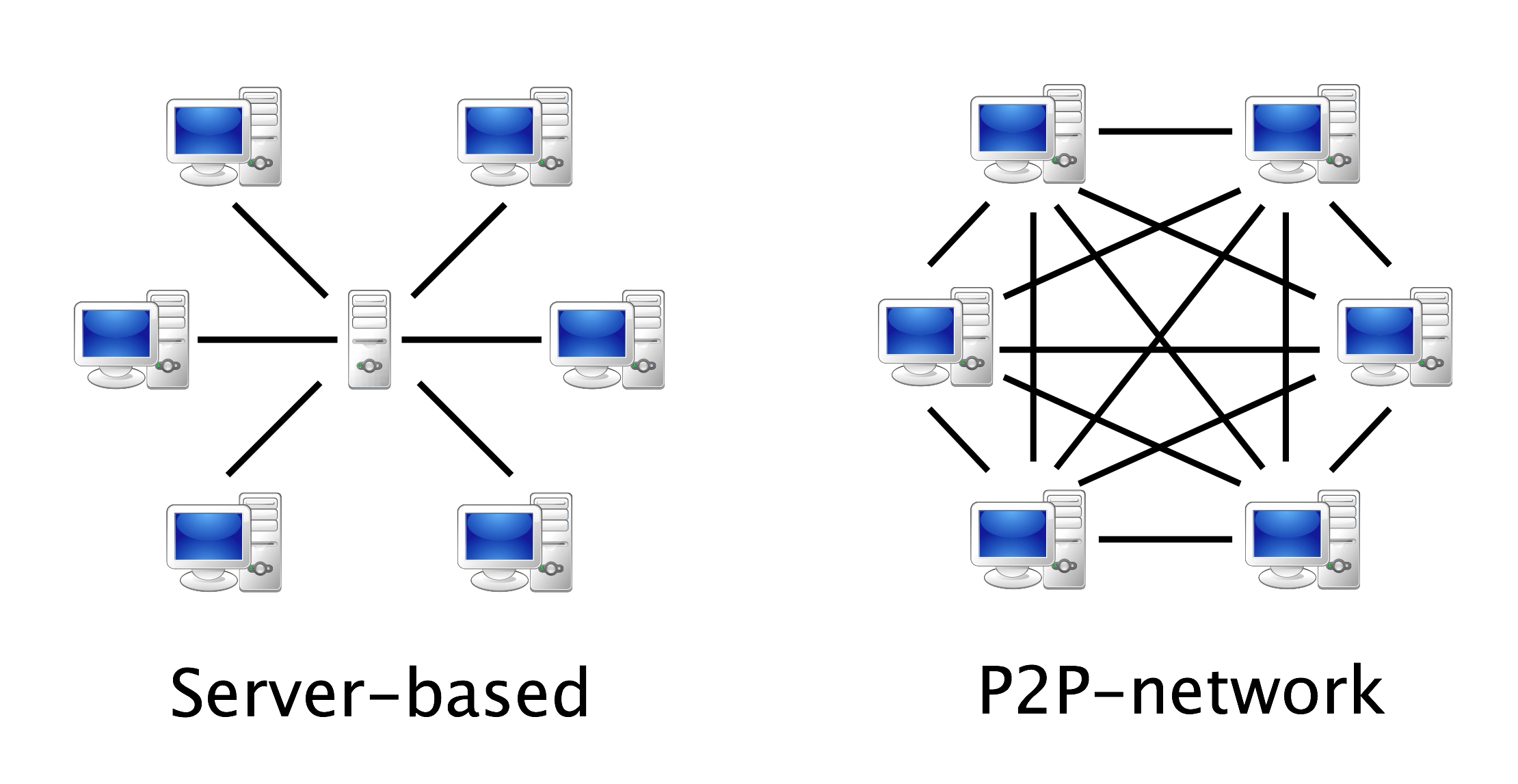

Syncthing is a file synchronization tool – much like Dropbox, but it is peer-to-peer, which means it works like Bittorrent or other file sharing tools that do not require a central server-based system to share files.

Why use Syncthing?

Firstly, Syncthing is an open source, peer-to-peer file sharing system, which means it is relatively cheap, simple to set up and secure. It is especially good for sharing very large files and collections of files without having to pay or to trust an intermediary to maintain a centralized file server. You run Syncthing on your computer, the person you want to share files with runs it on theirs, and you can set up folders that will synchronize files automatically when both your computers are turned on and connected to the internet. The data is encrypted in transit, and never sits on someone else’s server. Syncthing only requires each user to have a normal computer or laptop, rather than running on a server with each person using a ‘client’. This is more secure, and probably less complex to set up and maintain.

Secondly, Syncthing is open source, under active development and compatible with all major computing platforms because inevitably people will use Mac OSX and Windows, and sometimes *nix. Syncthing is one of many open source tools relevant for educational contexts, which are not only cheaper for individual researchers and teams, but also tend to stick around for longer.

Finally, Syncthing allows each user to choose how they want to organisze their folder structure. Whereas Dropbox uses a standard ‘dropbox’ folder, and (by default, at least) forces everyone use the same folder structure and folder names for their files, Syncthing allows you to put your data wherever you want on your hard drive, but still choose it as a folder to synchronize with your colleagues. So I may choose to put my video file in a folder on my Linux machine here:

/home/saul/data/project1/video1/video1.m4v

while you might have your videos on your windows machine at

C:\Users\Yourname\projects\project1\videos\video1.m4v

A third colleague may store video on their desktop (tut tut) on their Mac at:

/Users/user/Desktop/video files/video1.m4v

We can all then use Syncthing and choose to synchronize my ‘/video1/video1’ folder with your ‘\project1\videos’ folder and our colleague can synchronize with their desktop ‘video files’ folder – so despite us all having different data naming schema, we can collaborate effectively, share files, and keep our own file systems organized in a flexible and personalized way.

For many years I’ve used Dropbox but I’m always running out of space, then having to weed out awkwardly placed or duplicated files from collaborative projects which may or may not still be used or needed by collaborators. So this feature of Syncthing is a huge selling point for me.

What is Syncthing not so good for?

Syncthing is not particularly good for synchronizing millions of small, regularly updated files. Syncthing monitors which files need syncing by scanning its folders every few seconds to find out what has been updated – this can be a bit processor intensive if you have hundreds of thousands of files to scan through. So, it’s best to use it for projects with a few thousand large (especially video/heavy data) files rather than projects with tens of thousands or millions of files. For the same reason, if you need the files to remain synchronized in (close to) real-time, Syncthing’s folder scanning process will probably take too long.

Syncthing is not great for always-online files. Because it is a peer-to-peer system, Syncthing requires the computers you are keeping in sync to be online at the same time for syncrhonization to take place. Dropbox, by contrast, uses an always-online server, so it doesn’t matter if your multiple computers running Dropbox are online at the same time or not – the server will make sure they all have the most recent version of your Dropbox files. So, if you need something always-online, better to use a server-client system like Dropbox, OneDrive, iCloud etc.

Syncthing is not particularly useful on smartphones/tablets. Finally, although Syncthing does have an Android client and an iOS client, these are not officially supported by the same developers who work on syncthing, nor are they going to work if your computer is off-line when you need to grab a file via your mobile syncthing client.

Installing Syncthing

Syncthing has excellent, up-to-date documentation that will guide you through the installation process. However, there are also several helpful videos that will help you install Syncthing on different operating systems. I couldn’t find a video about how to install Syncthing on Mac OSX, so I made one myself.

Installing Syncthing on Mac OSX (with Homebrew):

Installing Syncthing on Windows

Installing Syncthing on Linux

Setting up and using Syncthing to share data

If you want to learn how to set up Syncthing for special purposes, and you want to explore all the options, I recommend reading the documentation, and if you want an in-depth video guide, I recommend the Nerd on the Street guide to setting up Syncthing. However, for a quick-start video, once you’ve installed it, I’ve created a short video that shows you how to use Syncthing to keep a folder in sync between two computers with the simplest set of default options.

I’ve used Mac OSX (el capitain) in this video, because I think it’s actually harder for most OSX users to understand how to fill in the Folder Path options (the location of the folder you want to sync) when setting up Syncthing for the first time. It’s relatively straight-forward to find Folder Paths in Windows and if you’re using Linux, I expect you’ll already know how to do that.

Troubleshooting

One major issue I’ve seen people having when running Syncthing for the first time is getting Syncthing to run at startup automatically. Although it’s beyond the scope of this article to deal with application startup issues – I’m happy to offer advice with this if you leave questions in the comments after reading the documentation.

Another major issue I had to deal with was cross-platform file-naming issues (especially for Mac OSX users). Basically, different file systems (FAT32, NTFS, exFAT, UFS/+, ext2/3 etc. etc.) allow different kinds of file names. If you are synchronizing folders between different file systems (on external drives, system hard drives, different operating systems etc.) it makes sense to use very conservative conventions.

I recommend the following:

- Do not use special characters, apostrophes, colons etc. in your file names.

- Use short, informative file naming conventions – include dates, project names etc. but do not use colons for times (like HH:MM:SS) as this will not work on many popular file systems.

- If you do have many existing files with these kinds of issues, try batch-renaming your files using OSX (Yosemite +) or using a batch file-renaming utility for windows (or the rename command on *nix).

Alternatives to Syncthing

There are many alternatives – some of them look very interesting, but none of them fit all the requirements outlined above as well as Syncthing. I’m open to adding to this list – so if you have a solution that isn’t shown here, please do let me know.

- Open Source (server based)

- Open Source (client/peer-to-peer based)

- Proprietary

- Promising (but not stable yet)

Finally – a very good solution, with minimum fuss or technology is to just copy your files onto small external hard drives and snail-mail them to each other in well-padded mailing boxes. That’s often a simpler (if slower) solution than setting up one of these systems!

How to share large amounts of research video data with Syncthing Read More »