AI and voice technologies in disability and social care

There is a crisis in social care for disabled people, and care providers are turning to AI for high-tech solutions. However, research often focuses on medical interventions rather than on how disabled people adapt technologies and work with their carers to enhance their independence.

This project explores how disabled people adapt consumer voice technologies such as the Amazon Alexa to enhance their personal independence, and the wider opportunities and risks that AI-based voice technologies may present for future social care services.

We are using a Social Action research method to involve disabled people and carers in shaping the research from the outset, and conversation analysis to examine how participants work together using technology (in the broadest sense – including language and social interaction), to solve everyday access issues.

The project team includes myself, Elizabeth Stokoe, Thorsten Gruber, Crispin Coombs , Donald Hislop, and Mark Harrison.

Relevant publications

Albert, S. & Hall, L., (2024) Distributed Agency in Smart Homecare Interactions: A Conversation Analytic Case Study. Discourse & Communication 18(6). 10.1177/17504813241267059

Hall, L., Albert, S., & Peel, E. (2024). Doing Virtual Companionship with Alexa. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.7146/si.v7i3.150089

Albert, S., Hamann, M., & Stokoe, E. (2023). Conversational User Interfaces in Smart Homecare Interactions: A Conversation Analytic Case Study. In ACM conference on Conversational User Interfaces (CUI ’23), July 19–21, 2023, Eindhoven, Netherlands. ACM, New York, NY, USA 12 https://doi.org/10.1145/3571884.3597140

Background

Voice technologies are often marketed as enabling people’s independence.

For example, a 2019 Amazon ad entitled “Morning Ritual” features a young woman with a visual impairment waking up, making coffee, then standing in front of a rain-spattered window while asking Alexa what the weather is like.

Many such adverts, policy reports and human-computer interaction studies suggest that new technologies and the ‘Internet of Things’ will help disabled people gain independence. However, technology-centred approaches often take a medicalized approach to ‘fixing’ individual disabled people, which can stigmatize disabled people by presenting them as ‘broken’, offering high-tech, lab-based solutions over more realistic adaptations.

This project explores how voice technologies are used and understood by elderly and disabled people and their carers in practice. We will use applied conversation analysis – a method designed to show, in procedural detail, how people achieve routine tasks together via language and social interaction.

A simple example: turning off a heater

Here’s a simple example of the kind of process we are interested in.

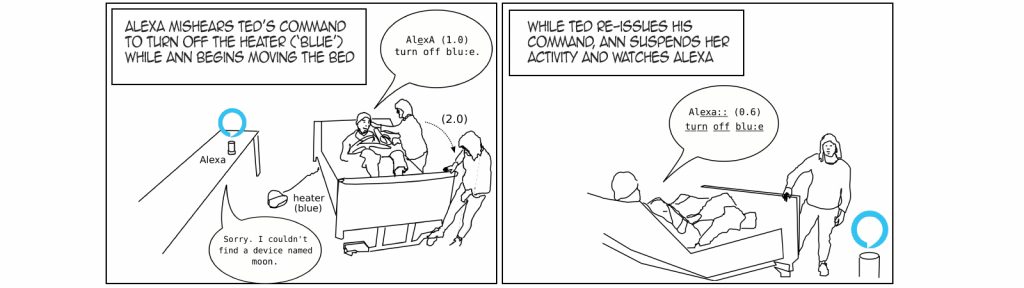

In the illustration below, Ted, who is about to be hosted out of his bed, gives a command to Alexa to turn off his heater (named ‘blue’) while his carer, Ann moves around his bed, unclipping the wheel locks so she can move it underneath the hoist’s ceiling track. Before Ann can move the bed, she has to put away the heater. Before she can put it away, it must be switched off.

Ann leaves time and space for Ted to use Alexa to participate in their shared activity.

While Ann could easily have switched off the heater herself before moving it out of the way and starting to push the bed towards the hoist, she pauses her activity while Ted re-does his command to Alexa – this time successfully. You can see this sequence of events as it unfolds in the video below.

Here are a few initial observations we can make about this interaction.

Firstly, Ann is clearly working with Ted, waiting for him to finish his part of the collaborative task before continuing with hers. By pausing her action, she supports the independence of his part of their interdependent activity.

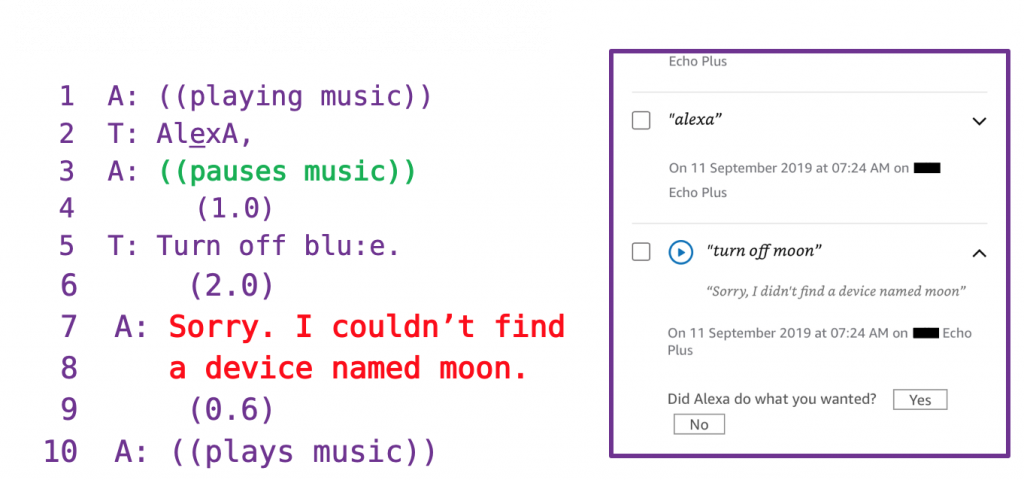

Secondly, using conversation analytic transcriptions and the automated activity log of the Amazon device, we can study the sequences of events that lead up to such coordination problems. For example, we can see that when Ted says the ‘wake word’ Alexa, it successfully pauses the music and waits for a command. We can see how Alexa mishears the reference to the heater name ‘blue’, then in lines 7 and 8, it apologizes and gives an account for simply giving up on fulfilling the request and unpausing the music.

These moments give us insight both into the conversation design of voice and home automation systems, and also into how interactional practices and jointly coordinated care activities can support people’s independence.

Thanks to

The British Academy/Leverhulme Small Research Grants scheme for funding the pilot project.